SSLS Blog Post: Noelle Lambert

My name is Noelle Lambert, and I am a rising third-year student at Georgia Tech. My majors are public policy and economics with a concentration in environmental and energy policy, so when I learned about an opportunity at the Center for Serve-Learn-Sustain, my interest was immediately piqued. Sure, I had taken classes familiarizing me with the principles of sustainability and how environmental justice influences policy, and vice versa, but potentially being involved with the tangible implementation of sustainability through technology was another thing altogether.

I wanted to focus my work on how technology impacts communities and why the technology even exists.

Sea level rise is an increasing threat every day as industries pollute more, individuals consume more, and decision makers continuously fail to take adequate action. However, given my background and passion for analyzing the practical effects that policy decisions have on marginalized populations, I wanted to focus my work on how technology impacts communities and why the technology even exists.

It quickly became clear to me that the Smart Sea Level Sensors are a highly important aspect of disaster preparedness and resilience. Savannah, Georgia is at the intersection of several pressing challenges: the issue of sea level rise exacerbated by global warming, natural disasters like hurricanes and intruding pollution from neighboring industries, shortages of quality food and affordable housing… the list goes on. I knew I could play a small, but potentially valuable role in helping with Savannah’s challenges. My supervisor, Allen Hyde, helped me better understand the issues at hand and hone in on specific work to be done.

The first piece of my work was understanding the social, economic, and environmental context of the area. I have worked closely with Allen, Nick Deffley, and Meaghan McSorley on the Community Engagement team to create and provide resources for the Harambee House, the first of which was a condensed version of the Community Profile Report of the Hudson Hill Community. The document serves as an in-depth resource for local actors like government agencies and nonprofits to analyze the potential impacts of policy decisions. My job was to examine this document to create a more accessible resource for community members, as well as decision makers to contextualize the area to create impactful policy. The most important facts and narrative based information were prioritized and organized into: social, environmental, housing, transportation, and health categories.

My biggest takeaway from this task was truly understanding objectives beyond checking a box. Sure, it may have taken a few hours to skim through the entire report and pick the most seemingly notable statistics. But, if the audience is a member of the neighborhood picking up a flyer, a local member of the city council reading a policy memo citing research, or a student perusing the SSLS blogs, each word matters. Savannah lies at the center of several historical and deeply systemic problems, but it is also a beautiful community. It has experienced poverty, chemical runoff, and food deserts, but also is the home to a plethora of churches, community centers, home-owning families, and frequently used public transportation systems. Those statistics are just as important.

After the community profile, my team and I began to focus on the health assessment: identifying academic resources connecting the major pollutants emitted by industrial plants in the Hudson Hill area to negative health ailments. My research started out very broad: I simply tried to compile as many papers as I could that maximized the number of pollutants and the number of ailments. From there, I cut down my list prioritizing concise yet informative sources, organizing them by strength of link and length. My final deliverable was a literature bibliography explaining different concepts like each chosen pollutant and ailment and exposure range, and organization, a bulleted explanation and analysis of each source, and a final table of all of the data compiled.

While my contribution to the health assessment did not include research on specifically the Savannah area, it is important to look at general sources connecting pollutants and their effects on a population. And, just like the community profile report, the health assessment can be used by many different actors for many different purposes. Sometimes, the condensed version of a lot of complicated information can be even more helpful than hundreds of pages of equally important research, but in complicated and inaccessible verbiage.

Overall, my work with the Smart Sea Level Sensors Community Engagement team was enriching largely due to my team. My team helped me with any questions I had, and encouraged me to take a task and run with it. If I had a different idea about how to complete a project, or even ideas about their own projects, that kind of creativity was encouraged. And this is an idea that Georgia Tech proliferates in other research and general studies.

What is community engagement, and why is it important to SSLS?

Introduction

Typically, when most people hear about the Smart Sea Level Sensors (SSLS) project, they are dazzled by the innovative sensor technology and data visualization tools, as well as the incredible educational programs that support sensor implementation. But perhaps less well-known is the hard work that the team has invested in community engagement since the project’s inception. The purpose of this blog post is to clarify the role of the Community Engagement (CE) team in the SSLS project, and to share some of the projects that we have worked on over the past several years.

My name is Meaghan McSorley, and I’m a third year PhD student in the school of city and regional planning. I work with Dr. Nisha Botchwey at the intersection of public health and urban planning. My research focuses on the “people side” of sustainability, and the question of how we can plan for healthy, equitable, and thriving cities for all. I’ve also been a member of the SSLS Community Engagement (CE) team since last summer. I had the opportunity this summer to work with the City of Savannah through the Serve-Learn-Sustain internship program. As a part of this blog post, I’ll share a bit about what I worked on this summer specifically, as well.

What is Community Engagement?

Before we dive into all of the projects that our team has worked on, it’s important to understand what we mean by ‘community engagement.’ There are many definitions available, and also a fair amount of disagreement among different disciplines. There are also adjacent terms like outreach, inclusion, and participation that are often deployed in these conversations.

To our team, community engagement is primarily about building relationships, and includes any activities designed to engage members of the public around issues of climate change, sustainability, resilience, and environmental justice. Community engagement is important because it not only provides the team with better information as we develop solutions around climate change issues, but also because it provides opportunities for residents and other community members to begin developing their own ideas about how to address these issues.

Our team also defines ‘community’ quite broadly. Our project team includes members of the Savannah local government, and non-profit leaders, both of whom constitute forms of community. The SSLS project also engages students, teachers, and residents, who also constitute additional communities. Our team hopes to engage broader and broader publics in our work and to create more opportunities for resident engagement and collaborative leadership over time.

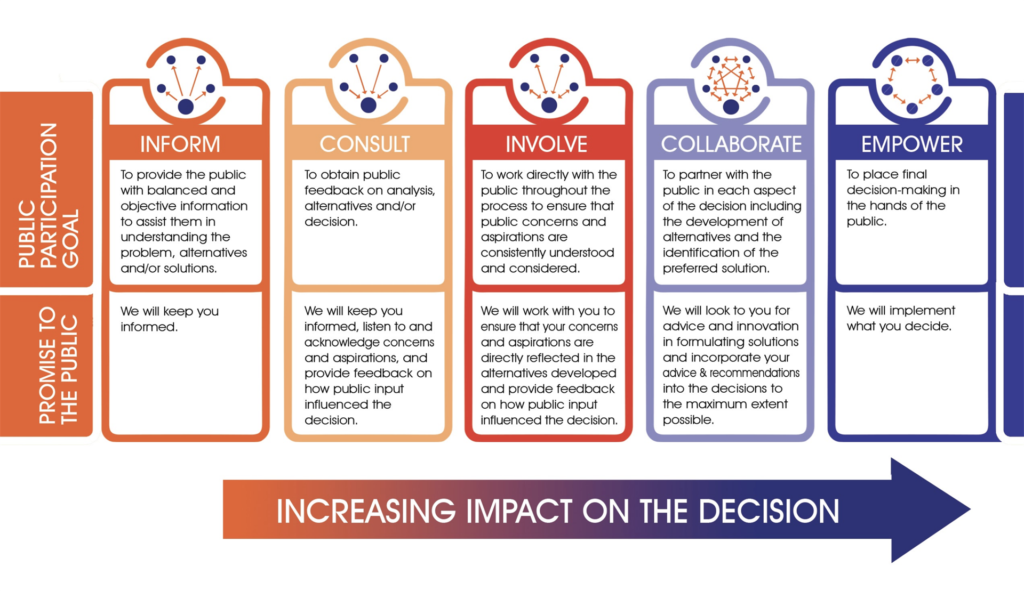

It is important to briefly ground those two definitions in some broader theory. There are many different forms, styles, and levels of community engagement. This means a diversity of approaches and activities to choose from. Perhaps the easiest and most important way to understand community engagement is that it is a spectrum, which moves from little public involvement to substantial public involvement. The following graphic comes from the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2), though it has intellectual heritage in the work of Sherry Arnstein (1969) and other scholars.

Moving towards greater empowerment is nearly always the goal because it grants more power to the public in directing decision-making. However, it takes time to build towards empowerment. Establishing trusting relationships, finding common language, and building the skills and knowledge of community members, as well as of project team member knowledge and skills about working with the community are all important steps towards empowerment that must be in place first. As such, it’s common for engagement activities to take place across the spectrum under a variety of different circumstances.

SSLS Community Engagement Team

There are many forms of community engagement present within the SSLS project. The project grew out of conversations between members of local government and Georgia Tech faculty, which itself shows how the very roots of this project grow out of collaboration with one form of community. The educational programming is another example of how the project has a sustained commitment to involving the broader public in the project.

The Community Engagement (CE) team includes students and faculty from Georgia Tech, staff from City of Savannah, and representatives of the Harambee House Citizens for Environmental Justice, a Savannah-based non-profit organization dedicated to activism and advocacy around issues of environmental justice.

Much of what our team has been doing so far has been about building relationships. The way that we do this is by listening deeply to learn about the various communities in Savannah and their needs and desires and developing research products that support both local government in engagement, which supports residents in community advocacy. This has included engaging with residents, non-profit organizations, as well as coordinating with other departments at the city.

Specifically, the CE team has conducted an in-person collaborative map-making workshop as a part of the Map Room; archival research; as well as quantitative social scientific investigation of publicly available data. We have developed surveys and other tools to support the City in engaging the public – for example, around a neighborhood emergency preparedness plan, which was also developed by this team. The team has also produced a community profile; the promise inventory; a brief air quality health assessment on two neighborhoods; and an engagement brief to support the City’s 100% Clean Energy plan development process. We have created opportunities for master’s, undergraduate and high school students. Members of the team have also participated in the installation of a gateway and temperature/humidity sensors, as well as assisted the Harambee House in deploying and calibrating PurpleAir sensors that provide a topic to encourage community science. The team has also developed several project proposals and participated in grant-writing efforts.

My work this summer has focused on the health assessments and the Clean Energy engagement brief. Last summer, the Harambee House had requested that some general information about the connections between various health conditions and pollutants be summarized, and that locally available data around these pollutants and health be aggregated into a report. My role was to turn their ask into a specific set of tasks that could be carried out by the undergraduate interns, to provide resources and feedback, to write a cover page which summarized the work and included additional health-related information to contextualize the report. I also edited the final versions of the reports, which pulled together the information from each of the undergraduate interns, as well as my cover page.

I also conducted a literature review to develop a brief engagement plan for Nick Deffley, for the City’s 100% Clean Energy planning process, occurring later this year. The engagement plan included a list of resources to enhance engagement broadly, but also with a specific focus on the populations of interest for this plan; as well as resources that were specific to engagement around clean energy and other sustainability initiatives. In addition, the engagement plan included a list of suggested activities and methods for engaging the focus group populations, which included small to medium size businesses, large firms, industry, frontline or vulnerable communities, and youth. I also reviewed the public-facing survey and developed some additional and alternative questions for Nick to choose from in the next phases of engagement.

Next Steps

Much of the team’s work so far has been focused on Hudson Hill, a low-income, historically Black community on Savannah’s west side that is surrounded by heavy industry. Hudson Hill residents do not typically struggle with flooding, which has sometimes made the CE team’s involvement with this neighborhood confusing. However, the reason that the CE team has done so much work with this community is that the Harambee House has a close relationship Hudson Hill residents and neighborhood leadership. Additionally, Hudson Hill has very active residents who have been advocating for environmental justice in their community since at least 2002, which means that they have been quick to engage on a variety of projects.

As the team began to look towards the future of the SSLS project and our engagement work, it became clear that identifying an additional community to work with was an important next step. We wanted to bring our work into closer alignment with the broader SSLS project by choosing a community that struggled with flooding. The Harambee House requested that we put together a health assessment for Ogeecheeton, and through collaboration with SSLS team members working on sensor placement optimization, we were able to identify a group of neighborhoods that included Ogeecheeton as our next focus area. This group of neighborhoods appeared as a great ‘next best’ location to place a sensor, and so it is our team’s hope that we can support having a sensor placed there. We would love to turn the sensor placement into an engagement and educational opportunity for the community and look forward to collaborating with the sensor team on this.

Rain Gauges, Dashboards, and Cellular-Capable Sensors: My Summer on the SSLS Team

I’m Mark Leggiero – one of two interns named ‘Mark’ working on the Sensor Development Team for the SMART Sea Level Sensors (SSLS) project. I am a senior at Georgia Tech with a dual major in Mechanical Engineering and Physics, and this is my first semester interning with Serve-Learn-Sustain, the Institute for People and Technology, or SMART Sea Level Sensors!

Starting Off – Adapting to my Project

I’ve made great strides in growing my technical skills throughout this summer internship. Most of my previous experiences in sensor networks came through working on robots and automated systems during internships, courses, and personal projects (which mostly just required knowledge of mechanical systems and design). However, my work with SSLS has been focused on software development, and therefore I’ve had to become more adept in this field. To this end, I’ve learned a great deal about software development and communication protocols.

Adding Rain-Gauges to Understand Rainfall

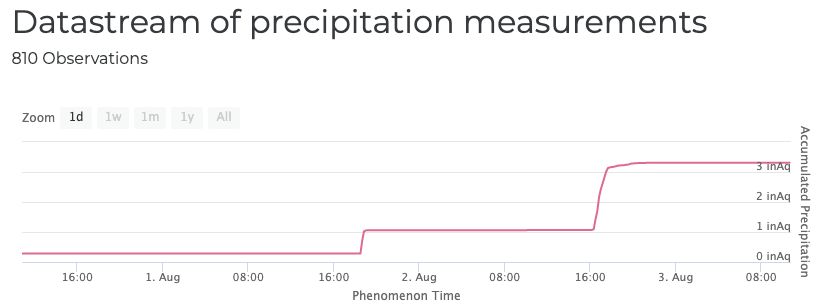

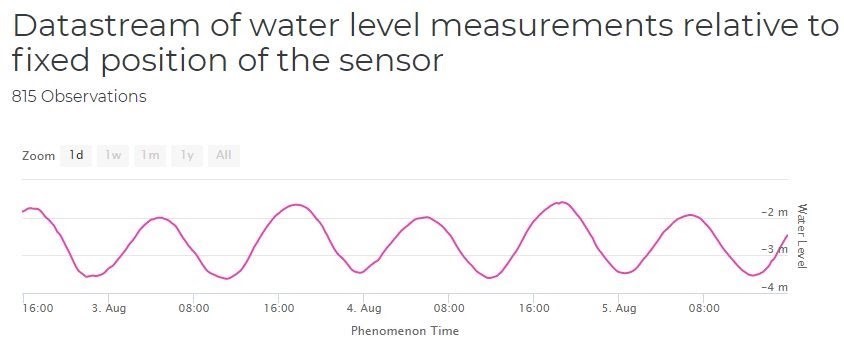

The SMART Sea Level Sensors project manages a wide network of water level, temperature, pressure, and air quality sensors. My work began as the project leadership identified measuring rainfall as a logical next step to improve their capabilities. Understanding rainfall, for one, can help disaster management in Chatham County better understand which areas are experiencing heavy storm events. Additionally, this can aid in climate research, where rainfall presents an important factor in properly modeling flood events. It is fair to say that most of this variation in sea level comes from the ocean’s tide, however this isn’t the entire picture. Rainfall, inlet river flow, and other factors also affect water level in the region, especially as one looks further away from the coast.

Our first step was a market analysis for commercially available rain gauges. Through comparing 25+ models of rain gauges, ranging in technologies, prices, accuracies, etc., we selected Hydrological USA’s TB4 gauges. Currently, the project uses custom electronics (developed by Georgia Tech researchers Scott Gilliland and Peter Presti in collaboration with the Institute for People and Technology) to send data from the water level sensors to the dashboard using an ESP32 (a commonly available microprocessor) and LoRaWAN chip (Long Range Wide Area Network – a low-power radio communication protocol). A significant percent of my work this summer was spent getting the existing hardware to function with the TB4 rain gauges. Our largest challenge was ensuring that the updated firmware functioned in a manner which required as little power as possible, since the sensor units are run on batteries.

Initially, we hoped the software we developed would allow us to use either a water level sensor or rain gauge, but given the simple operation of the TB4 (a tipping-bucket rain gauge), we were able to update the firmware of the LoRaWAN hardware to collect both rainfall and water level data concurrently and through one unit.

Since completing the first stable version of the new LoRaWAN firmware, we have deployed three units attached to rain gauges for testing (at the time of this post, each is labeled as a “Pre-Deployment Validation”). They are functional and uploading concurrent rainfall and water level data to our dashboard at their respective locations in Atlanta and Savannah:

Cellular-Capable Sensors

Transitioning from the rain gauges, the Sensor Development Team started work on implementing hardware which can send sensory data to the dashboard while only requiring a cell connection. This is mostly helpful in areas where radio communication (such as that used by the LoRaWAN board) is not very effective – including regions with a dense tree canopy. Scott and Peter have developed such a board, which is similar to the LoRaWAN unit, but requires different methods for developing its firmware. Namely, the heart of the board, the nRF9160 chip, can be programmed with custom software provided by Zephyr.

After successfully communicating with the nRF9160 chip, the team worked on understanding how the board would send data to the dashboard. We selected the MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) communication protocol for sending sensor data, and use an open-source MQTT library, Mosquitto. We were able to accomplish sending pe-determined messages from the cellular board to a web-server we hosted on a low-cost Raspberry Pi 4B computer (used mainly for testing).

The next step for us is to write a program that allows the board to collect sensory data, starting with water level, and convert the data into a suitable message for MQTT. Given differences between LoraWAN and nRF9160 boards, setting up serial communication between the nRF9160 and ultrasonic sensor had been a challenge. Our final work on this board has been understanding the nRF9160 and Zephyr serial interface, and documenting our progress for whoever picks up this work in the future!

Concluding Thoughts

As mentioned near the beginning of this post, I learned a lot of valuable technical skills during these 12 weeks on this project. I am proud of what the Sensor Development team accomplished, especially since rain gauge units were able to be deployed. However, I want to appreciate the multidisciplinary aspects of the project (which were beyond my work). The SMART Sea Level Sensors project could have been counted as a ‘success’ if it stopped at environmental monitoring, however, through the vision of the project leadership (Dr. Kim Cobb, Dr. Russ Clark, Randall Matthews, Nick Deffley, and others), they have impacted the Chatham / Savannah area in numerous ways, emphasizing social justice. I have grown to admire, and hope to emulate, their forward-thinking in this area.

Lastly, I want to specifically thank Mark Putman, Dr. Russ Clark, Scott Gilliland, and Peter Presti for a meaningful internship experience!

Building a tool that helps track flooding

Hi, my name is Austin Ang!

I am a rising 3rd year majoring in Computer Science at Georgia Tech, but I was born and raised in Savannah, GA. I first learned about the Smart Sea Level Sensors team through the public school system here in Savannah. During my time at Jenkins High School, I worked on this project during the construction phase, helping build one of the initial waves of sensors. I’m really glad to be able to hop back in and work on it again during my time at Tech.

I’m building a tool that helps people track flooding.

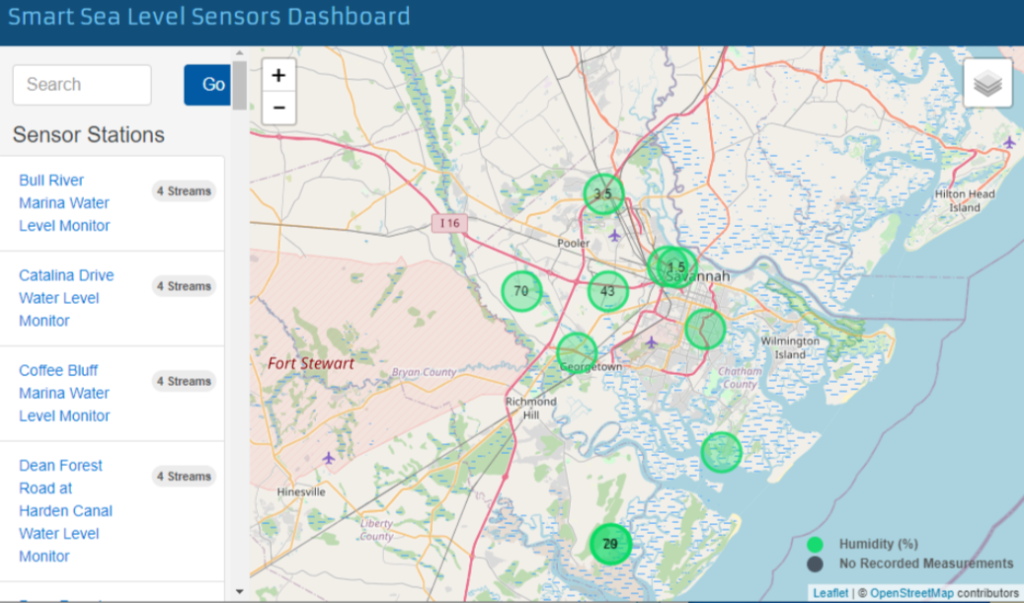

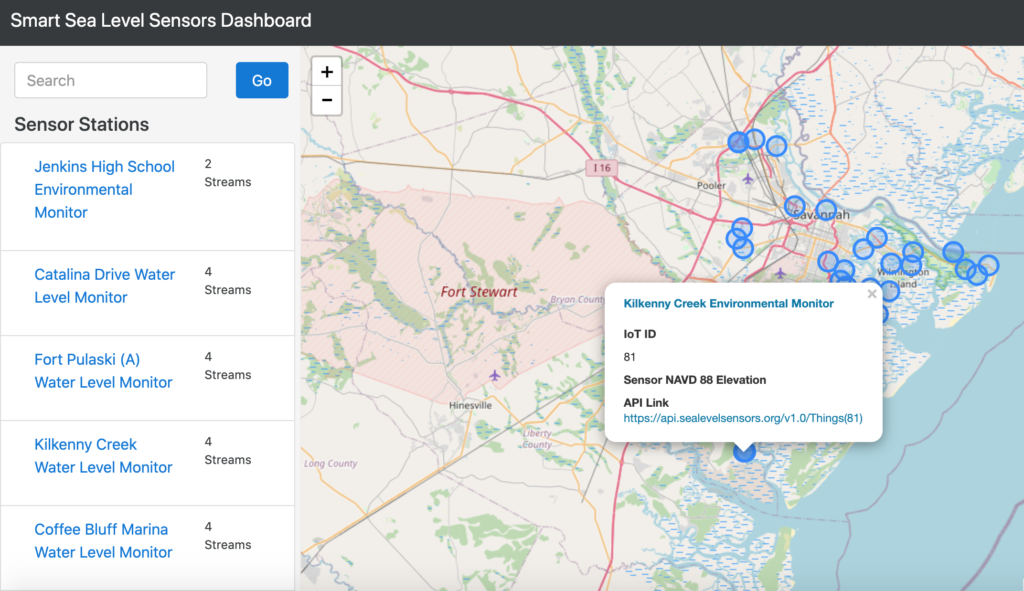

In high school,I constructed the actual pieces of sensors, assembling them with a team of classmates. Now, I’m working on the public facing dashboard: the dashboard is a publicly accessible website that anyone on the internet can use. It shows the sensors we have installed and the information that we learn from them. For the Smart Sea Level Sensor project, I’m using javascript to make the dashboard easy to use, part of my job is making sure that the data is present that the public would like to see most.

Starting out, it was pretty daunting…

Even though I’m a CS student, I needed to learn web development for this project. It was daunting to look at this well-established codebase and try to make sense of it. I spent a week or two seeing what each function did, and even when I thought I had it figured out, it would end up surprising me down the road! At first, it would take me days to make changes that I thought would be relatively simple, and that was frustrating, but I knew that with time most problems can be solved. Adding layers (like street maps and buildings) to the dashboards and updating the corresponding legends on this map was one of my first goals. Afterwards, I implemented a solution to find the last sea level measurement taken within a certain time period and have it appear on the map. This makes the data more accessible for users, so they don’t have to click on a sensor to see the water level measured there.

Why does it matter to me?

Climate Change. Those two words are so important, especially during the time that I am writing this. As a Savannah resident born and raised here I have seen the sea level rise issue and flooding as a major problem. I remember many times during hurricanes Matthew and Irma where we had to completely drop what we were doing in high school and evacuate the area. The idea of potentially losing our homes was terrifying and I wouldn’t wish that fate upon anyone else. This project matters to me because it could make a difference in a future hurricane / flood situation and mitigation of damage for my hometown is something I hope for.

What’s Next?

At the time of writing this, I just volunteered to help with the Georgia Tech IoT camp. It was really fun teaching kids about technology, showing them technologies extremely similar to what we use in the sea level sensors project, and helping to create the next!

Virtual Community Engagement During a Pandemic

My name is Alyson Laura, and this summer was my final semester of graduate school in the Sustainable Energy and Environmental Management (MSSEM) program within Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy. I heard Dr. Cobb speak about the Smart Sea Level Sensor (SSLS) project through Drawdown Georgia. In my world of healthy communities, climate policy, and regenerative systems, these are the two most important research projects happening during my short time at Georgia Tech. I took advantage of all my opportunities exclusive to students and applied for a summer internship through the Serve Learn Sustain (SLS) internship program.

Receiving the invitation to join the SSLS team in Summer 2020 was a dream come true. It was a chance to participate in deeply inter-disciplinary work with awarded academic researchers, seasoned emergency management officials and professionals across local municipalities and national government agencies on climate policy research. It perfectly aligned with my career goals to be a climate leader in the Southeast.

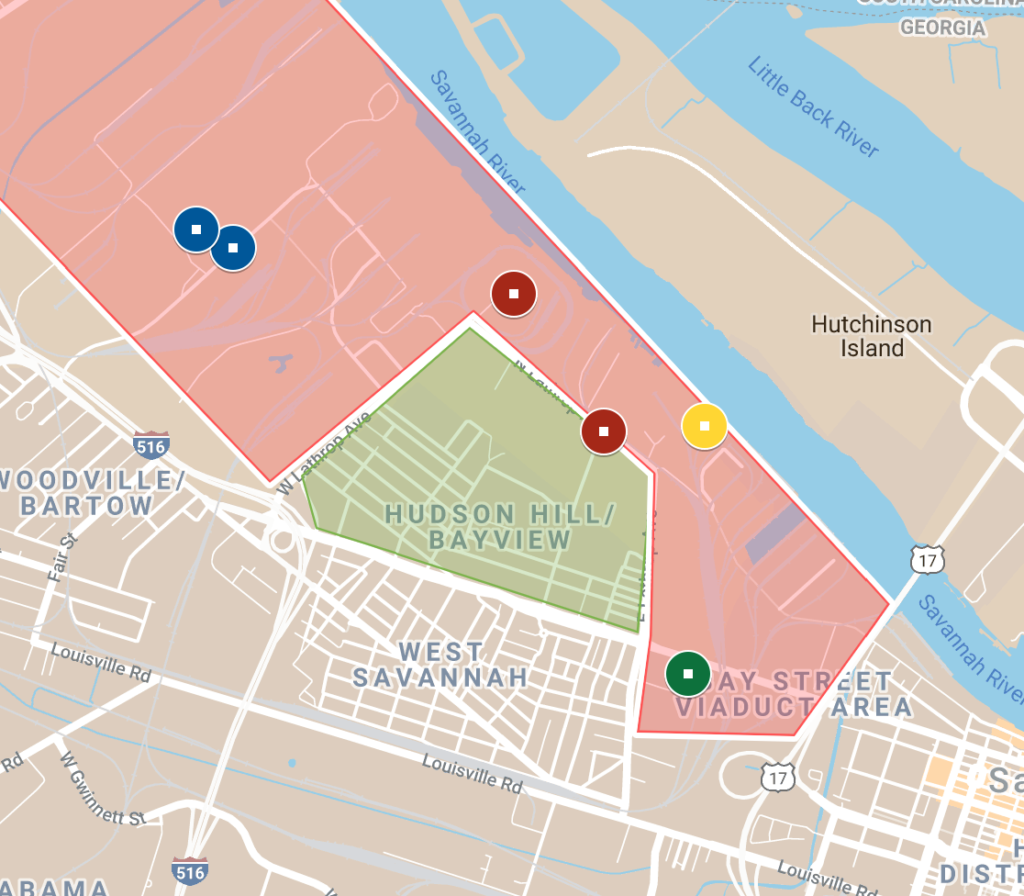

My specific role was assigned to the community engagement workgroup. Our work focused on neighborhood scale emergency response and preparedness through the City of Savannah’s Office of Sustainability. The specific neighborhoods of Hudson Hill, Bayview, and Clearview are located near the Savannah Port, in an Environmental Justice (EJ) community. They partner with the EPA through their non-profit advocate, the Harambee House, and the City of Savannah.

With so many partners at the table with a vulnerable community, I knew I was in for a tough assignment. But no one could have predicted the challenges presented by the global pandemic that broke out just before my internship started.

There would be no more in person community engagement. Citizen science air quality monitoring training sessions were held virtually. Meet and greets with community leaders occurred over the phone. And my tour of the city sustainability office has to be done with a mask on.

Rather than hitting the streets, I was deep in documents and internet searches to quickly get up to speed on emergency preparation and hazard assessments. The community I engaged in was less community members and more academics and EPA experts. The humor of emergency planning during an emergency was not lost on our team and we marched on making progress behind the scenes.

Interning on a project that hits close to home

My name is Patrick Daugherty, I’m an upcoming 5th year undergrad at Georgia Tech getting my degree in Environmental Engineering with a minor in Environmental Science. After I graduate I am planning to go to graduate school and get a masters degree in hydrology or water resources engineering. I’ve always wanted to work in the environmental field since I was a kid so to be able to work on a project like Smart Sea Level Sensors is truly a privilege.

How I learned about the Smart Sea Level Sensors project

I first became aware of the Smart Sea Level Sensors project a few summers ago when Dr. Clark asked to put a receiver for the water level sensors in the attic of my parent’s house on Hutchinson Island in Savannah, Georgia. As an upcoming sophomore in Environmental Engineering at Georgia Tech I was immediately interested in getting involved on a project concerned with sea level rise, a topic that was relatively new to me since coming to college but one that seemed to be at the fore front of my attention not only in many of my classes but especially considering my home in Savannah, where sea level rise poses a looming threat to my family, my friends, and my community.

It took me a while to find an opportunity to get involved in the project but fast forward two years and I am taking an excellent class about sustainability and energy taught by Dr. Cobb and it’s brought to my attention that the Smart Sea Level Sensors project is looking for interns. I immediately applied because I knew that I would be working on would be something I was passionate about even if it wasn’t strictly about sea level rise because any environmental issue in Savannah is an issue that I want to concern myself with.

My Team

To be frank, I didn’t really know what to expect going into this internship. I had never really worked on a project like this before but I was excited and optimistic to get to work on a project located squarely in my community. Fortunately, I landed on team that has guided me along the way to succeed in my role and have helped me so much in such a short time. I report to Nick Deffley, the Sustainability Director for the City of Savannah, who has been such a great resource for me in this internship in guiding me through it but also in serving as a career mentor. He has contributed greatly in helping me decide where I want to take my career and has given me a valuable glimpse into the work of sustainability and environmental justice in the public sector. My fellow intern on the project that I work beside, Alyson Laura, has been excellent in that regard as well and I’m lucky to be able to work so closely with someone like Alyson. Her experience has been an invaluable resource to me and I can’t think of where our project, the Hudson Hill Community Profile Report, would be with out her working on it.

The Hudson Hill Community Profile Report

The project that I am working on this summer is the Hudson Hill Community Profile Report, a report lead by Dr. Allen Hyde, a Georgia Tech professor in the school of history and sociology, about the community and people of the Hudson Hill area including the Bayview and the West Savannah area. This report is meant to serve as an account of the facilities and services available to the people that live here as well as to asses the unique vulnerabilities that the community faces due to their location. This area is located in very close proximity to many of Savannah’s heavy industries and is subject to very poor air quality as a result along with a number of other problems that this proximity creates. In addition to serving as a profile of the community on the surface, this report is meant to highlight and bring attention to these environmental injustices faced by the residents of the area. Learning about this community that I have lived so close to all my life but have been so aloof to the problems they faced has been truly eye opening for me. I live less than half a mile away from the area the report concerns and I can attest to the low air quality environment that the heavy industry creates so to talk about their air quality being poor when a large portion of these people’s homes are less than an eighth of a mile away from industry is a massive understatement.

I think this graphic does a good job at displaying the point I’m trying to make here. I’ve lived in Savannah my entire life and I had no idea that there was a neighborhood not only so close to the industry on the Savannah River but nestled almost entirely inside it. The air quality and noise pollution in the neighborhood have immediate and long term health consequences and their hasn’t been much done in the all but very recent past to address these problems. I hope that this report and this project can help contribute to finding a long term solution to these injustices faced by the people of Hudson Hill and it has been a privilege to work on it.

A glimpse into the life of an Air Quality Intern

My name is Kaylyn Sinisgalli. I’ll be graduating from Georgia Tech in the fall with a degree in Environmental Engineering and this summer I’m interning with the SMART Sea Level Sensor’s project on the Air Quality team. Working with the SMART Sea Level Sensor’s Air Quality team is not my first Georgia Tech SLS experience and I hope it won’t be my last!

How I became an SLS Intern

I’ve been involved with SLS since its inception which happened to be my first semester at Georgia Tech. I was a part of the first SLS GT-1000 course in the Fall of 2016 which hooked me for more SLS experiences. In the spring of my second year I participated in the first edition of “Serve-Learn-Sustain in Spain,” the GT faculty lead study abroad program to Granada, Spain in the spring of 2018 with Dr. Kelly Comfort. My SLS study abroad program was my first real introduction to community lead projects. As a part of the program, we were required to take a service-learning course (definitely one of the most valuable courses I have taken at GT!) and design a service-learning project around a community organizations (some of my work is pictured below).

Although I had to leave Spain, I did not leave behind the impacts my service-learning project made on me. I experienced the value added to work when the work was driven by a community need and I knew I wanted to continue to be a part of community-driven projects in the future.

As I’m graduating in the fall, I wanted to spend my last summer interning with a community-based organization. While in Sea Level Rise and Costal Geotechnics, a SLS affiliated course co-taught by Dr. Alex Robel and Dr. Jorge Macedo, I had the pleasure of listening to Dr. Cobb speak about her SMART sea level sensors project, which inspired me to apply for SLS internships.

I’ve really enjoyed working with the team this summer! Due to COVID-19 I am working remotely, but I’ve still been able to learn so much and communicate with team members easily. I’m enjoying the work-life balance I’ve had this summer by working remotely and am thankful for the extra time I’ve been able to spend with my family without a commute!

My Intern Experience

I think my biggest take away from this internship experience thus far has been tremendous growth in my technical skills. Coming into the internship, I had some coding experience from previous internships and projects, but I did not have experience with leveraging REST APIs or python, both of which are crucial elements to the work I have done this summer.

For those of you who are unfamiliar as I was at the beginning of my internship, API stands for “Application Programing Interface.” APIs provide a set of documented ways to interact with and retrieve data from a database. The SMART Sea Level Sensors team is developing an API to store the sea level sensor data; similarly, PurpleAir, in addition to the PurpleAir map which allows you to manually download spreadsheets of data for a certain monitor label, has a historical API, Thingspeak, which allows users to access numerical and metadata recorded from every public sensor.

I’ve really enjoyed learning how to get data from APIs through pulling West Savannah PurpleAir data. By working with an API through Google Colabs, I haven’t had to store any of the data I’ve observed on my PC and I’ve been able to run my scripts on Google’s clusters, making my code run much faster than it normally would. I’ve also set the Colab notebook (it works just like a jupyter notebook and can be downloaded directly as a py file which is awesome!) to save any charts I export directly to the Air Quality Team Drive, making it easy for everyone to see what I’m working on.

If you want to practice pulling PurpleAir data yourself, I created a Colabs notebook to walk new user through the process. It can be found here! Feel free to reach out to me with questions! They also have awesome resources on their website if you want to start by pulling Excel files.

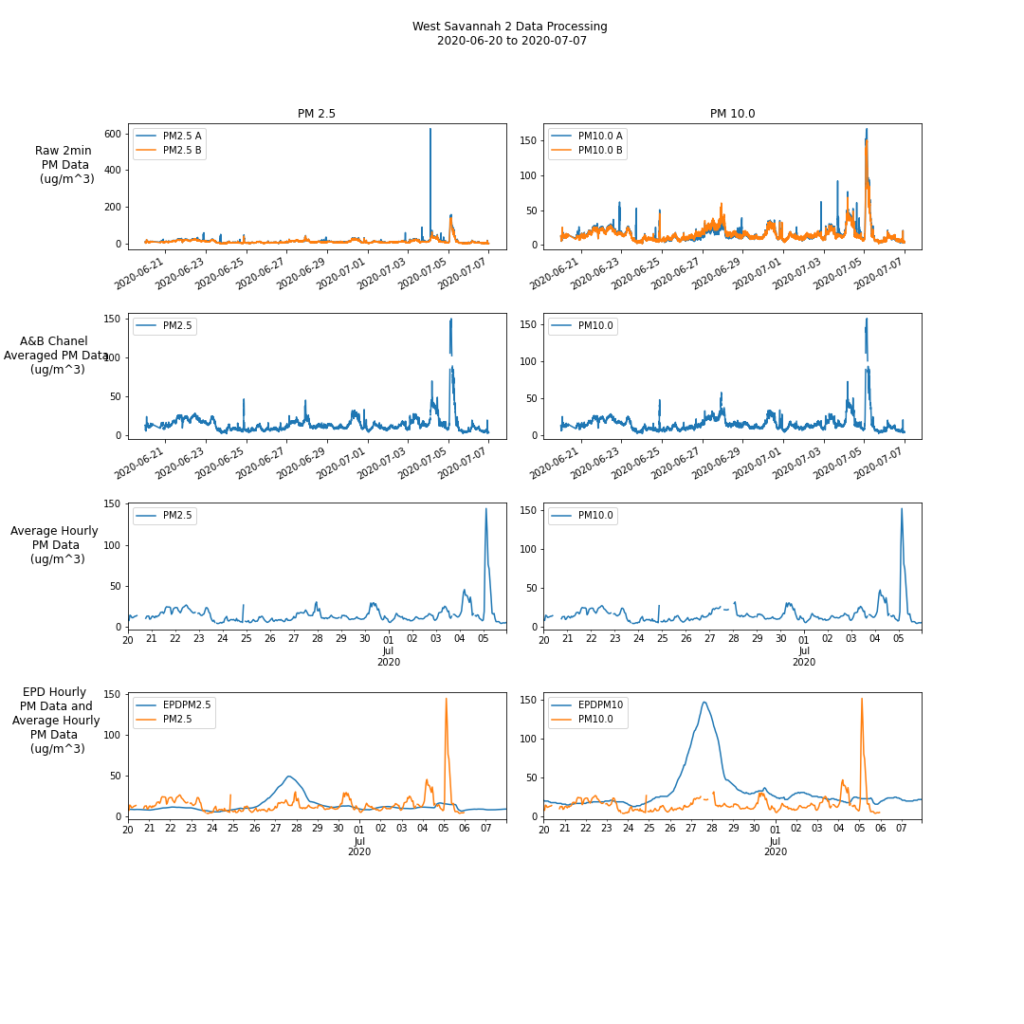

My main goal for this summer is to calibrate the PurpleAir sensors with the EPD air quality monitor at the L&A site in Savannah. Dr. Clark worked with our contacts in Savannah to place four PurpleAir monitors at the EPD site in Savannah. In theory, the PurpleAir monitors should report the same PM concentrations the EPD reports, as the devices are co-located, but in reality, a correction factor may be needed. I’m working with Dr. Russell Clark, EPD contacts, and Sea Level sensor team members to figure out the best way to do this.

Sensor Labels: West Savannah 1,2,3,& 5

Just as the PurpleAir data can be accessed through an API, EPD data can be pulled using an API as well. I’ve created a script to pull data from the same time frames and compare the two data sets which has allowed me to visualize the two data sets together. When looking through the data, I’ve enjoyed looking for real life events in the PM trends. See if you can spot 4th of July fireworks and the Saharan Dust Cloud in the data below in the PM data in the graphs below! (keep in mind the data is in GMT, so you need to subtract 4 hours, so 8 pm on the graph is 4pm EST!)

I’m sad there is only a month left in my internship! I’ve really enjoyed my time thus far with the SMART Sea Level Sensor team. I’m looking forward to the Hurricane Conference at then end of the month and the remaining bi-weekly team calls. Last week I was able to present to the whole team and our partners on what I’ve been working on this summer – the presentation is linked here.

My First 6 Weeks as an SLS Intern

My name is Benjamin Vaisberg and I am a senior at Georgia Tech studying computer science. I was born in Venezuela and raised in Miami, Florida. The Sea Level Sensors project caught my attention because I think it’s something that Miami will need sooner rather than later. Although I wasn’t born here, I consider Miami my home and it’s very concerning to see that sea level rise isn’t as big as an issue as it should be. I thought SSLS was the perfect way for me to get involved in a project that could have a positive impact on my own community.

I’m coming up on 6 weeks working as a Software Engineer for the Sea Level Sensors. This is basically the halfway point of my internship here. I’ve learned a lot of things that I expected to learn and others that I didn’t expect so much. Some of these expected things I learned include a lot of technical skills like Python and Javascript. Although I already knew these things coming in, I’ve definitely developed these more as I’m working with certain libraries that I had never used before. My first task was to update a program that had already been written and get it working again. The project was an anomaly detection program for the sea level sensors. The gist of the program was to get data from the Sensors API, fit it with the NOAA sensor at Ft. Pulaski, and flag any measurements that were above or below a certain threshold. This seems pretty straightforward when read like that. But when I started looking at the code and the flow of the program, things got a lot tougher. It was hard to follow the execution of the tasks and the program would take a long time to run. It was a few days where I didn’t write a single line of code because I was just trying to understand the program. Once I did, I was able to make good contributions to the anomaly detection program. I updated the cache to include a database so that the program would run much faster. I also fixed a lot of the errors that were happening because of date formatting and tried to include more documentation so that whoever continues this project can do so more easily.

The second task I had was to update the Sea Level Dashboard. The goal of this was to make it more user friendly for the general public. Some of the things we thought to do were to include information on the main page rather than having to click through a few times before finding relevant information. While this dashboard still has some ways to go, I’ll be asking for some feedback from its users so I can continue working on it.

Going back on some of the things I learned are the things that I didn’t really expect to learn or probably hadn’t really considered. I think there are 2 main things I learned that are the most important. The first one is that everyone does something with a purpose and everyone has different ways of approaching things. This I realized when I was looking at the anomaly detection program. At first glance, I wanted to do an entire rewrite of the program. It wasn’t making any sense to me how this program worked. However, the more I looked into it the more I kept saying to myself “ah that’s clever”. This was important to me because as a developer there’s a lot of times where adding to someone’s code is necessary so understanding the original intentions and ideas is important rather than coming in closed-minded with my own ideas. The second thing I learned was which stems off from the first one is that spending time to understand the problem makes the problem easier in the long run. This was something that was hammered onto us pretty consistently at Tech and I was glad to see that it holds up anywhere. If I would have just started coding right away, I would have never understood how the program works.

Overall, it’s been a really good experience especially because I can do my job 100% from home and I am not limited whatsoever. As long as I have my computer, I can pretty much get anything done on a daily basis which is already a huge win considering everything going on around us.

I’m looking forward to 6 more weeks like the first 6!